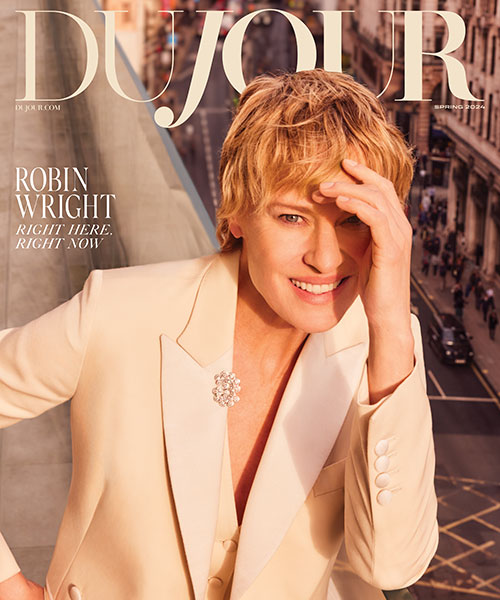

Scooter Braun doesn’t do anything small. He’s got big lips, big money and a big office inside a gut-renovated West Hollywood compound. Textured wallpaper, plush couches and framed gold records from clients like Justin Bieber, Ariana Grande and Cody Simpson mingle with black-and-white photos of Braun hobnobbing with the likes of Magic Johnson and Whoopi Goldberg. But what really stands out about the space is the Executive Robot parked next to the 34-year-old Braun’s desk. Imagine a Segway with a computer screen for a face and you’re halfway there.

“I log on from my laptop anywhere in the world and suddenly my face comes on the screen. I control its movements. I can see everything,” he says. “We have meetings where I’m like, Get the whole staff in the office. In the beginning you feel awkward. And after 20 seconds, you think I’m in the room.”

Awards he’s won for work with artists like Cody Simpson

It’s a fitting metaphor, considering Braun doesn’t just have his finger on the pulse of culture, he’s got it on the carotid artery. In a short time, Braun has established himself as the wizard controlling what’s in our earbuds and, increasingly, what’s on our screens. Beyond Bieber’s six number-one records or Ariana Grande’s role as pop’s reigning diva, there’s Braun’s first foray into producing scripted TV, CBS’s Scorpion, which last year averaged more than 10 million viewers weekly. He’s hoping that same magic strikes when Jem and the Holograms, which he produced, hits theaters this fall. Braun’s also expanding into tech—he’s an investor in Uber, Pinterest and Spotify—and politics, having hosted a $2,700-a-plate August fundraiser for Hillary Clinton. Braun’s so on it these days that no less than L.A. Reid recently told Billboard: “Scooter Braun could do anything.”

And he’ll have to. Despite Braun’s Millennial Midas touch, there seems to be a disconnect between his public persona (and the perception that he’s Bieber’s babysitter or, worse, his enabler) and his private self. Braun hasn’t always helped matters, memorably telling The New Yorker in 2012 that he’d bought his neighbor’s house so he could knock it down and install a basketball court in its place. And yet this morning, he looks less like a mogul than the friendliest dad at day care. He’s dressed in Chuck Taylors and dark jeans. And those lips are smiling big as he pulls out his iPhone to share a photo of his son, Jagger, in a diaper, with sweatpants draped around his ankles. Braun—who married Yael Cohen, co-founder of the nonprofit Fuck Cancer, in 2014—explains with a laugh, “I was changing his diaper and he started crying. I was like, You want to fight me on the pants? Fine. The pants are staying off.”

By now Scott Braun’s origin story is the stuff of legend. A dentist’s son from Greenwich, Connecticut, enrolls at Emory University but rarely goes to class, concentrating instead on selling fake IDs to rich kids—the same ones who’d later need those IDs to get into the parties he was promoting. “If these kids were gonna throw money around,” Braun says, “I was gonna catch it.” He starts calling himself Scooter (a childhood nickname) full-time, and by age 20 he’s dropped out and become the head of marketing at Atlanta’s So So Def Records, where—in a move sure to be taught in business school someday—he cold calls Pontiac and secures a $12 million campaign for Ludacris. Braun soon goes out on his own, signing a Canadian kid named Justin Bieber from YouTube. Looking back, he explains: “I couldn’t wait to get out of Greenwich. I wanted to start over.”

The accolades and ephemera that decorate Braun’s office

What fueled that fire is less known. “My grandfather was a Holocaust survivor,” Braun says. “My grandmother worked in a sweatshop. My dad went to Bronx Science and got scholarships and worked his ass off to give his family a better life. My mom’s dad died when she was 11, and she basically went on welfare. Here I am, first generation being handed something, and that drove me crazy.” Braun insisted on creating his own obstacles. “All I wanted to do was prove I could become something.” Why stop at music? “I’m having fun,” he says, “but I want so much more.”

As his younger brother Adam Braun (whose nonprofit, Pencils of Promise, builds schools in developing countries) recalls, it was only a matter of time. “Scott was always the most socially gifted person in every room,” he says. And the elder Braun isn’t afraid to put his business where his mouth is. At a gala for Pencils of Promise, Scooter suggested his client Martin Garrix contribute a DJ set to the auction. “That item alone helped build more than three schools,” Adam says.

There’s a sign behind Scooter’s desk that reads, “Create, Execute, Deliver.” And if you squint, you can see a through-line between the young man who admits to throwing a few punches in his youth and the highly evolved mogul sitting here today. Braun’s gift is zeroing in on what the public wants before they even know they want it. With Top 40 radio populated by over-produced acts, he’s pushing Tori Kelly, a sort of neo-Jewel for Millennials too young to remember the Alaskan who lived in her van. And Braun’s got a nimble mind. After watching Kelly and her band rehearse for the Billboard Music Awards in May, he yanked her musicians from the stage and instead shoved the 22-year-old leggy blonde out there alone armed with only her guitar. It was a risk to go so low-tech on national TV, but the verdict was immediate. John Legend tweeted, “Tori Kelly with the vocal performance of the night.”

Braun backstage with Tori Kelly at The Wiltern in Los Angeles

While breaking new artists is crucial to a manager’s reputation, so is keeping a star from going supernova. Bieber’s implosion has been so well documented, it’s amazing that we’re now talking about a comeback and not a stint on Dancing with the Stars. That’s a testament to how well orchestrated the Justin Bieber Apology Tour has been. Braun’s team at SB Projects came up with the idea to do a Comedy Central Roast, which let Bieber speak to his demo directly and show he was in on the joke. Meanwhile, Bieber’s ride in James Corden’s Carpool Karaoke (28 million hits on YouTube and counting) reminded us the kid could sing. Now he’s in the studio working with Kanye West, Rick Rubin, Skrillex and Diplo, and Braun, who used to wait by the phone every night until he heard from Bieber’s bodyguards, says, “You know how much easier it is for me to go to sleep now? It’s fantastic.”

That’s Braun: Part-time Svengali, full-time sweetheart. As for the basketball court he was going to build on his neighbor’s property, that’s ancient history. “I met my wife and realized I didn’t want to be a bachelor anymore,” he says, almost annoyed at the line of questioning. “People want you to fit into a stereotype for what that entertainment guy is. I want to create a new stereotype. You can be very successful in this business and be a good person and a good husband and a good father. You don’t have to be that asshole.” Besides, he’s on to bigger real estate deals, reportedly dropping $13.1 million on a seven-bedroom, 11,000-square-foot house in Brentwood last year, which he tore down to the studs. Says Braun with a grin and an awesome what-do-you-want-from-me shrug: “The bones were great.”

With that, Braun’s buzzing phone can no longer be ignored, and an assistant hovers by the door waiting to pounce. Before departing, Braun makes his ultimate ambition clear, smiling as he says, “I gotta be relevant when my kid’s a teenager.”